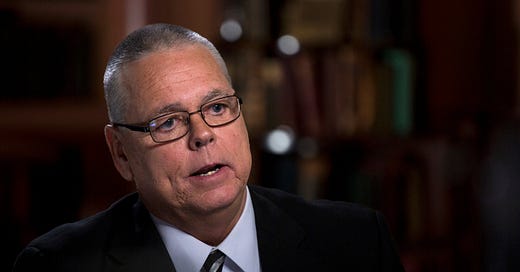

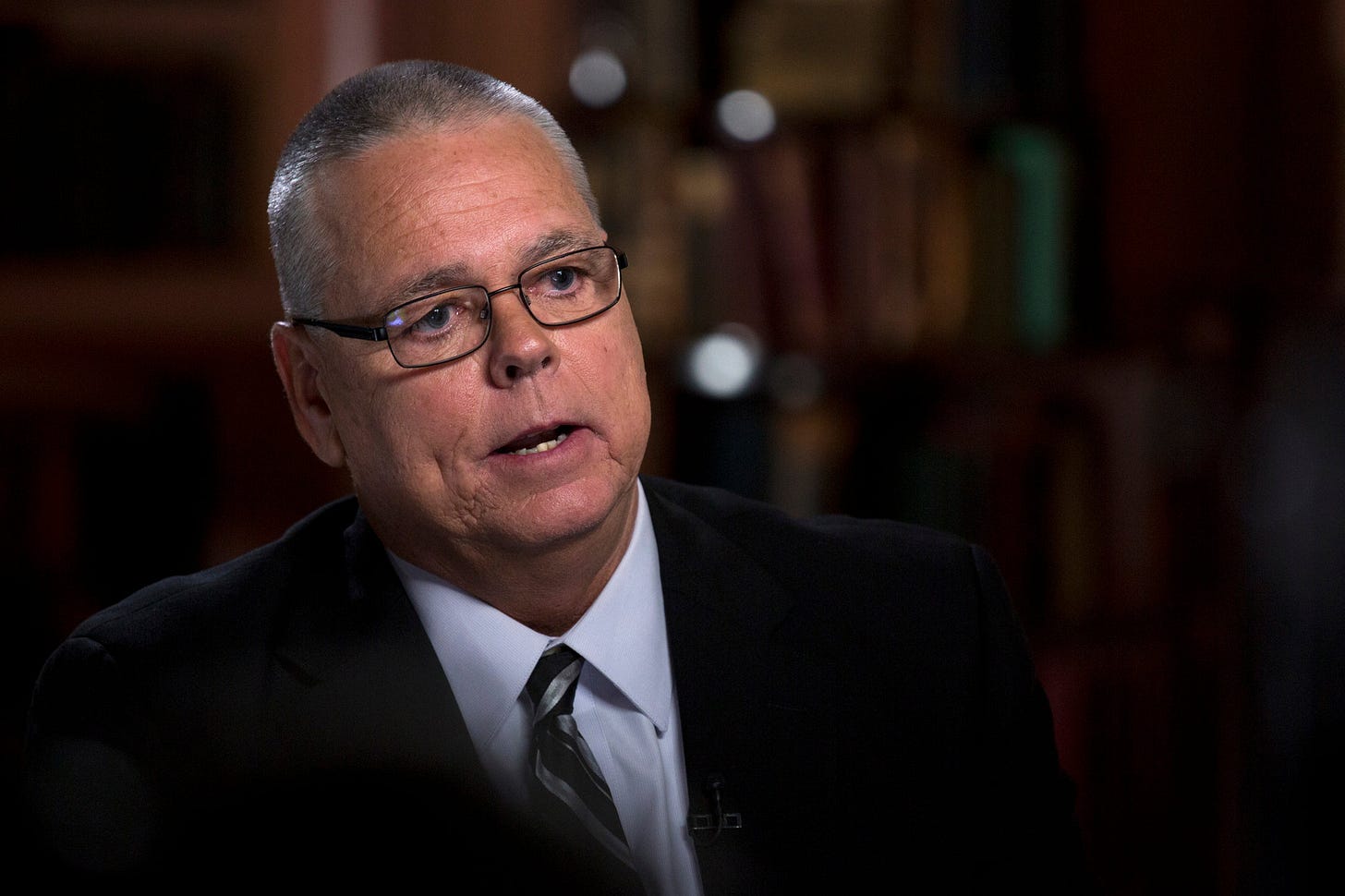

When the news broke that a law enforcement officer (school resource officer) refused to enter Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida to engage school shooter Nikolas Cruz, many in the public demanded the law enforcement officer lose his job. It's been over three years and Officer Scot Peterson, who faces 11 charges including child neglect and endangerment, still has not been inside a courtroom to face these charges.

In my opinion, if this were not such a hyper-political case, he never would’ve been charged. Why you ask? Because of legal precedent.

Warren v. District of Columbia (1981)

Warren v D.C. is probably the most cited case when it comes to the fact that police aren’t mandated to protect the individual.

The details of the case are terrifying:

In the early morning hours of Sunday, March 16, 1975, Carolyn Warren and Joan Taliaferro, who shared a room on the third floor of their rooming house at 1112 Lamont Street Northwest in the District of Columbia, and Miriam Douglas, who shared a room on the second floor with her four-year-old daughter, were asleep. The women were awakened by the sound of the back door being broken down by two men later identified as Marvin Kent and James Morse. The men entered Douglas’ second floor room, where Kent forced Douglas to perform oral sex on him and Morse raped her.

Warren and Taliaferro heard Douglas’ screams from the floor below. Warren called 9-1-1 and told the dispatcher that the house was being burglarized, and requested immediate assistance. The department employee told her to remain quiet and assured her that police assistance would be dispatched promptly.

Warren’s call was received at Metropolitan Police Department Headquarters at 0623 hours, and was recorded as a burglary-in-progress. At 0626, a call was dispatched to officers on the street as a “Code 2” assignment, although calls of a crime in progress should be given priority and designated as “Code 1.” Four police cruisers responded to the broadcast; three to the Lamont Street address and one to another address to investigate a possible suspect.

Meanwhile, Warren and Taliaferro crawled from their window onto an adjoining roof and waited for the police to arrive. While there, they observed one policeman drive through the alley behind their house and proceed to the front of the residence without stopping, leaning out the window, or getting out of the car to check the back entrance of the house. A second officer apparently knocked on the door in front of the residence, but left when he received no answer. The three officers departed the scene at 0633, five minutes after they arrived.

Warren and Taliaferro crawled back inside their room. They again heard Douglas’ continuing screams; again called the police; told the officer that the intruders had entered the home, and requested immediate assistance. Once again, a police officer assured them that help was on the way. This second call was received at 0642 and recorded merely as “investigate the trouble;” it was never dispatched to any police officers.

Believing the police might be in the house, Warren and Taliaferro called down to Douglas, thereby alerting Kent to their presence. At knife point, Kent and Morse then forced all three women to accompany them to Kent’s apartment. For the next fourteen hours the captive women were raped, robbed, beaten, forced to commit sexual acts upon one another, and made to submit to the sexual demands of Kent and Morse.

Warren, Taliaferro, and Douglas brought the following claims of negligence against the District of Columbia and the Metropolitan Police Department: the dispatcher’s failure to forward the 6:23 a. m. call with the proper degree of urgency; the responding officers’ failure to follow standard police investigative procedures, specifically their failure to check the rear entrance and position themselves properly near the doors and windows to ascertain whether there was any activity inside; and the dispatcher’s failure to dispatch the 6:42 a. m. call.

The women sought to sue the District of Columbia and several individual members of the Metropolitan Police Department on two different occasions. The results were:

“In a 4–3 decision, the District of Columbia Court of Appeals affirmed the trial courts’ dismissal of the complaints against the District of Columbia and individual members of the Metropolitan Police Department based on the public duty doctrine ruling that ‘the duty to provide public services is owed to the public at large, and, absent a special relationship between the police and an individual, no specific legal duty exists.’ The Court thus adopted the trial court’s determination that no special relationship existed between the police and appellants, and therefore no specific legal duty existed between the police and the appellants.”

Town of Castle Rock v. Gonzales

The importance of Castle Rock v Gonzales cannot be overstated since, unlike Warren, this case was taken to the Supreme Court of the U.S.A. for its ruling.

The events that precipitated the ruling are tragic to say the least:

During divorce proceedings, Jessica Lenahan-Gonzales, a resident of Castle Rock, Colorado, obtained a permanent restraining order against her husband Simon, who had been stalking her, on June 4, 1999, requiring him to remain at least 100 yards (91 m) from her and her four children (son Jesse, who is not Simon’s biological child, and daughters Rebecca, Katherine, and Leslie) except during specified visitation time. On June 22, at approximately 5:15 pm, Simon took possession of his three daughters in violation of the order. Jessica called the police at approximately 7:30 pm, 8:30 pm, and 10:10 pm on June 22, and 12:15 am on June 23, and visited the police station in person at 12:40 am on June 23. However, since she from time to time had allowed Simon to take the children at various hours, the police took no action, despite Simon having called Jessica prior to her second police call and informing her that he had the daughters with him at an amusement park in Denver, Colorado. At approximately 3:20 am on June 23, Simon appeared at the Castle Rock police station and was killed in a shoot-out with the officers. A search of his vehicle revealed the corpses of the three daughters, whom it has been assumed he killed prior to his arrival.

Gonzales filed suit against the Castle Rock police department and three of their officers in the U.S. District Court of Colorado claiming they didn’t protect her even though she had a restraining order against her husband. The officers were declared to have “qualified immunity” and thus, couldn’t be sued. But, “a panel of that court… found a procedural due process claim; an en banc rehearing reached the same conclusion.”

In this case, the government of the town of Castle Rock took the decision against it to the Supreme Court of the U.S.A. and got the procedural due process claim reversed, finding:

“The Court’s majority opinion by Justice Antonin Scalia held that enforcement of the restraining order was not mandatory under Colorado law; were a mandate for enforcement to exist, it would not create an individual right to enforcement that could be considered a protected entitlement under the precedent of Board of Regents of State Colleges v. Roth; and even if there were a protected individual entitlement to enforcement of a restraining order, such entitlement would have no monetary value and hence would not count as property for the Due Process Clause.

Justice David Souter wrote a concurring opinion, using the reasoning that enforcement of a restraining order is a process, not the interest protected by the process, and that there is not due process protection for processes.”

Lozito v. New York City

This one was saved until the end because, unlike the previous cases, the officer in this one admitted under grand jury testimony that the reason he didn’t come to the aid of Joseph Lozito is because he was scared that Lozito’s attacker had a gun.

On February 11th, Maksim Gelman, started a “spree-killing” by stabbing his stepfather, Aleksandr Kuznetsov, as many as 55 times because he refused to allow Gelman to use his wife’s (Gelman’s mother’s) car. Gelman would end up killing 3 more while injuring 5, the last injured person being Joe Lozito on a northbound 3-train while on his way to work.

The facts of the Lozito attack are startling:

“Joseph Lozito, who was brutally stabbed and “grievously wounded, deeply slashed around the head and neck”, sued police for negligence in failing to render assistance to him as he was being attacked by Gelman. Lozito told reporters that he decided to file the lawsuit after allegedly learning from “a grand-jury member” that NYPD officer Terrance Howell testified that he hid from Gelman before and while Lozito was being attacked because Howell thought Gelman had a gun. In response to the suit, attorneys for the City of New York argued that police had no duty to protect Lozito or any other person from Gelman.”

Lozito had heard of the previous cases stating that the police had “not duty to protect” but decided to go to court representing himself.

The court would have none of it:

“On July 25, 2013, Judge Margaret Chan dismissed Lozito’s suit, stating that while Lozito’s account of the attack rang true and appeared “highly credible”, Chan agreed that police had “no special duty” to protect Lozito.”

As segments of the country protested, rioted and looted as a “response” to the George Floyd video last year, and local governments questioned the funding of their enforcement agencies, people should’ve taken a macro view of their “protection services.” While some rightly railed against police brutality and aggressive policing, they should’ve went back to the beginning and asked whether any of these “fixes” being proposed would actually work if the most basic assumption when it comes to “serving and protecting” is a farce.

If the police are just there as a clean-up crew, or historians after the fact, why not designate them as such. If in the overwhelming amount of cases they get there after a crime has been committed, it’s time to take that 2nd Amendment seriously and remove the barriers that keep many people, especially those in high crime areas, from protecting themselves. “Armed” with the knowledge that those you have falsely believed were there to protect you are in fact serving another purpose, rational individuals should be looking for realistic options when it comes to protecting yourself from any threat that may come your way; public or private.

Great post. That first case discussed is precisely why I’ll encourage any and everyone to completely ignore whatever make believe firearm restrictions the gooberment will try and impose on you.